Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

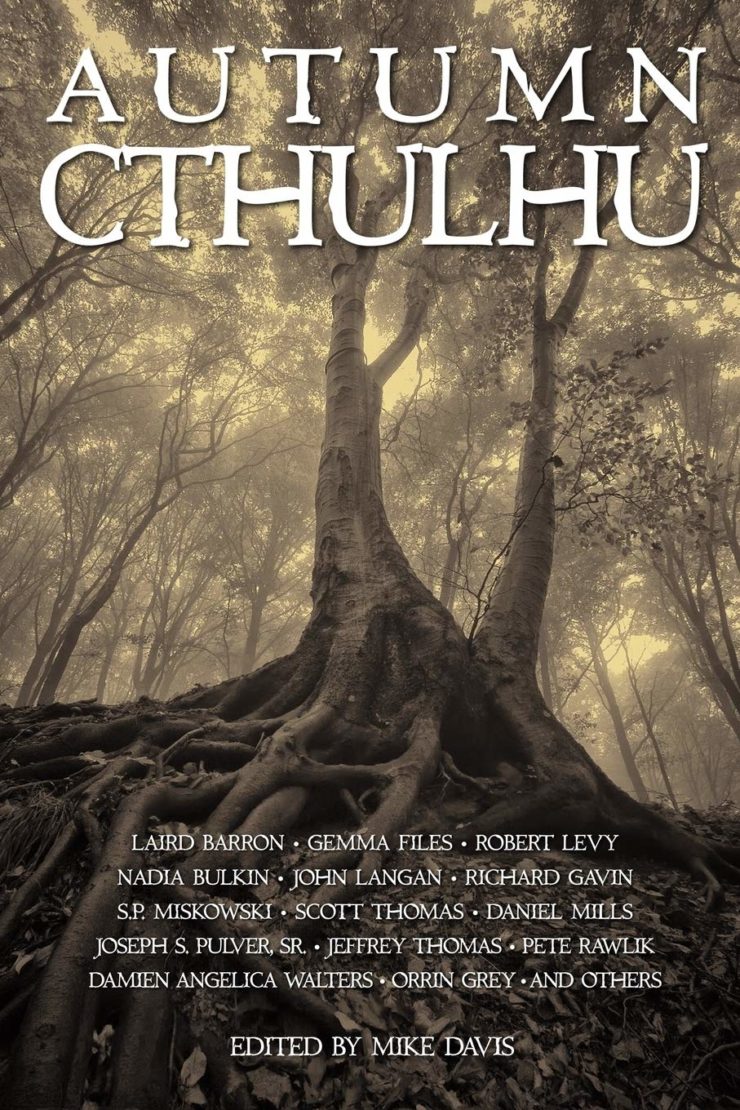

This week, we cover Robert Levy’s “DST (Fall Back,” first published in the Mike Davis’s 2016 Autumn Cthulhu anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“Starlight and stridulations. Together they open windows. But only inside the gifted hour.”

Unnamed narrator drives to Milford in late October, summoned by former romantic rival Martin. Ten years earlier, Martin and Narrator’s ex Jasper moved to small-town Pennsylvania; narrator hasn’t seen either since. He barely recognizes the haggard-faced Martin—maybe Jasper has finally broken his heart, too.

Well, sort of. They did break up, but now Jasper’s been missing for a month. This past year, Jasper’s been deteriorating. It started the morning he turned up unconscious and naked on their lawn. He started staying out nights. Martin assumed Jasper had a new lover, but then weirdly symmetrical round marks began appearing on his body.

The Jasper narrator knew wouldn’t leave the house if he detected a single blemish on his smooth skin. His stomach knots as he realizes how much he’s missed the guy.

Martin describes how Jasper moved into a “hovel” apartment, seeking uninterrupted time for a “new project.” He got fired from his dance studio, was repeatedly arrested for vandalism, trespassing, vagrancy. Last time Martin saw him, Jasper was staggering along the road, sunburned, clothes filthy. Martin urged him to get medical help, but Jasper refused. Martin, he said, couldn’t understand what he was going through. Only narrator might understand, when “it was time.” Then Jasper had said something about a disco race?

Narrator recognizes reference to a favorite techno album from his college gig as a late-night DJ: Disco Death Race 2000. Jasper called the station to praise narrator’s taste, then popped over from the college dance center. That was an October night when daylight savings time kicked in, giving narrator and Jasper an extra hour for cramped sex under the sound board while he let the album play in full.

He and Jasper were a natural couple, often mistaken for each other. They wore the same clothes. They—fitted together.

Martin has no idea where Jasper’s gone, but he wants to show narrator something. They drive to the estate of a former governor, now open for tours. In a clearing in the nearby woods, suspended twenty feet off ground on iron pipes, is something like a wooden grain silo tilted 45 degrees from perpendicular. A rusted ladder rises to the narrow opening. Martin explains that it’s a cosmoscope, a sort of observatory long disused. Someone’s recently added rubber tubes to the exterior—supposedly they’ll transmit forest noises to the interior. How’s this relevant? Jasper was living inside the structure pre-disappearance.

Slim like Jasper, narrator enters the cosmoscope and explores a wooden labyrinth like “a canted rat maze.” Outside, he finds his hands smeared with something that smells like raw meat. Martin says he hoped narrator would understand WTF is going on. After all, Jasper said he’d tell narrator “at the right hour.”

Narrator spends the night at a nearby hotel. He feels drained and alone. He looks up the cosmoscope’s creator, George Vernon Hudson, best known for advocating daylight savings time. Then he collapses in bed. He wakes, per the bedside clock, at 2:59 am. The room’s cold. When he reaches for a lamp, a voice from the darkness says, “Don’t.”

It’s Jasper who’s clambered through the window. He’s naked and emaciated, face bruised, round black marks on his torso and limbs. With little preamble, he begins talking about Hudson, the ridiculed visionary who finally prevailed. Hudson was entomologist as well as astronomer: you can’t glimpse the multitude of the heavens without listening to the multitude of the earth. And at the “gifted hour,” and “they” will let you see.

Buy the Book

A Master of Djinn

Jasper’s breath smells of the grave, but his caress still stirs. His tongue stings; his hand cups narrator’s skull as if he’s drinking from it. Manipulation of time, Jasper says. Their gift is our key, but only during the “twice-born hour.” As narrator struggles, the “small mouths” carved into Jasper’s skin spill black ooze that hardens into “gelatinous protuberances” pinning him to the bed. Their “thrashing tide” forces itself into narrator’s mouth and throat. Just before he passes out, he sees that the bedside clock still reads 2:59 am.

The next night, narrator returns to the cosmoscope and worms his way deeper into the interior maze. At last he reaches a coffin-sized recess in which he can stretch out on a pulpy surface moldable as sponge. Through the opening above, he sees a sky filled with stars impossibly close, “globules of fire.” The heavens rattle and hiss, tremble and strain, awakened to new life. The “uneven lurch of something crawling over dry leaves” signals Jasper’s approach, and through holes lining the pinnacle-chamber, narrator hears the insect-song of the forest. His skin hums, desperate for communion—“the total unity of matter that only oblivion could provide.”

The “nebular sky” rips open. The cosmoscope undulates and spins, and the thing of which Jasper’s become part seizes narrator with “a thousand hungry mouths.” He bleeds into its pain and rage and ecstasy, transmuting, becoming part of the greater whole, the same as Jasper, never to be apart again. He sees Jasper’s wry smile, is joined with him in yet another cramped space. They give themselves away, and what remains splashes the interior of the cosmoscope like “wet gristle in a mighty centrifuge.”

They are elsewhere now.

What’s Cyclopean: The language gets considerably more eldritch toward the end of the story: once Narrator is under Jasper’s spell, the stars are “smoking crystalline globules of fire” and the sky is “nebular.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Martin resentfully dismisses the 25-year-old “twink from Germany” who’s taken over his old maitre d job. Though his exasperation at “Have you heard of Nuremburg?” is understandable.

Weirdbuilding: A lot of good weirdness is built on a foundation of real history, and George Vernon Hudson—entomologist, astronomer, messer-up of clocks—provides an excellent seed.

Libronomicon: Less books this week, more albums: specifically Disco Death Race 2000.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Martin believes that Jasper is “losing his mind.” It would probably be more accurate to say that it was taken.

Anne’s Commentary

Sometimes it takes my brain a while to kick in. I puzzled over Levy’s title through my whole first reading of this week’s story. DST? Does that refer to something on the techno album narrator and Jasper favor? By the way, I’m listening to Disco Death Race 2000 right now via the magic of YouTube. I can hear why it would make a suitable soundtrack for messing around under the sound board of a college radio station circa 1996. It’s got a good beat, and you can dance to it, or engage in other rhythmic activities.

Then I wondered if DST was some kind of euphoria-producing drug. Then I read the story again, and it hit me. DST stands for daylight savings time, derp. And “fall back” comes from the mnemonic devised for those of us easily confused by time changes: Spring forward, fall back. See, in the autumn (aka fall!), you turn the clock back an hour! That’s because in the spring, you turn the clock an hour forward, and then you have to correct things come Octoberish, returning to what certain E. F. Benson characters called “God’s time.” Maybe real people irate about DST also say “God’s time,” I don’t know. EFB is good enough for me.

“DST (Fall Back)” features other real things besides the above-named album. Milford, PA, is real. The Hotel Fauchere in Milford, PA, is real. Grey Towers near Milford, PA, is real; and its owner Gifford Pinchot was real, and really the governor of Pennsylvania, first head of the U. S. Forest Service, and a founder of the conservation movement. George Vernon Hudson was a real astronomer and entomologist and crusader for DST, but I can’t (speedily) find that he ever visited Grey Towers or built a cosmoscope there or elsewhere. Nor does tourist information for Grey Towers mention a cosmoscope on its Forest Discovery Trail—surely it wouldn’t omit such an attraction!

Jasper connects George Vernon Hudson’s suitability for designing cosmoscopes to his being both an astronomer and an entomologist. This makes sense in that the word cosmoscope has a couple definitions. One, it’s an instrument designed to show the positions, relations and movements of celestial bodies, that is, an orrery. Two, it names a microscopic journey through tiny universes or worlds. Hence a cosmoscope may deal with the largest or the smallest realms tantalizing human curiosity. Or, as in Levy’s version, both realms at once, starlight AND stridulations. Together they open windows, but only in the “gifted hour.”

What’s the “gifted hour,” you ask? (I asked anyway.) Let’s return to George Vernon Hudson. By fourteen, he had amassed an impressive collection of British insects. Later, in New Zealand, he would put together the country’s largest insect collection, describing thousands of species. To catch that many bugs, the guy needed as much daylight as he could scrounge. Is this why, in 1895, he proposed adding a couple of hours onto warm (buggy) summer days? A gift of an hour is what we’ve ended up with, which becomes a “twice-born” hour when we switch back in autumn, 2 am getting a second chance at 3 am. Manipulation of time, Jasper whispers in narrator’s ear. That’s what gives us the key, enables us to open wide enough to give ourselves to the All!

If I haven’t thoroughly confused myself, that means that only in the autumn fall-back hour can the cosmoscope pull off its ultimate trick. Or can something also be done during the vernal spring-forward hour, another manipulation of time?

Never mind, we’re talking fall-back here, as, perhaps, into a falling back to primal conditions when the All was One, a singularity. Such an implosion would account for that sticky mess the cosmosphere gets itself into at the end of the story. Except it was a sticky mess when narrator first climbed into the contraption, I guess from Jasper’s ouchy-ecstatic moment of transmutation, and that couldn’t have taken place during the single fall-back hour of that particular year, which is when narrator joins him in the All-in-One.

Okay, confusion definitely looms on my mental horizon.

Here’s what I know for absolutely sure. The Grey Towers people should either tear down the cosmoscope or gift it to Miskatonic University, where they’d know how to deal with such an iffy device. I hear they have Yith connections at MU, and who better than the Yith to handle time-space manipulation? Could be the Grey Towers specimen is one of Their Own Works. Could be George Vernon Hudson spent some time as a Yith host between grubbing for grubs, in which case do we have the Yith to blame for DST?

There’s a scary thought to end with, and so I shall.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Daylight savings time is a human invention, and an annoying mess, and a source of endless argument about whether the benefits outweigh the harms, and I kind of like it. I used to only like the “fall back” night, when you get that precious extra “gifted hour,” but now that I have kids I also appreciate Spring’s opportunity to convince your offspring to shift to a more convenient wake-up time. But it is—as my kids point out twice a year—pretty confusing. Surreal, even—how can you get more time one day and have an hour vanish entirely another? Our temporal illusions are showing, and we hurry to tuck them back in.

(George Vernon Hudson probably didn’t travel fast enough to confront the weirder temporal breakdowns involved in a round trip between the U.S. and New Zealand or Australia, in which the shifted period is a day rather than an hour. I have met the international dateline and I do not like it.)

There must be magic in that DST change, right? Beyond the stage magic of changing our clocks? Magic, maybe, that could be done only in that extra hour. It wouldn’t be the only example of set-aside periods in which the impossible becomes possible. Inversion festivals are common enough—many cultures seem to have a sense that the rules of orderly life are made more bearable by a Carnival or a Halloween. Maybe that yearning for a turn-everything-upside-down-and-inside-out break extends to the laws of physics, too, and to the very stuff of selfhood.

Levy’s story, while not overtly featuring Cthulhu, appears in the Autumn Cthulhu anthology. The book’s title is easy to gloss past, on a shelf that includes Cthulhus new, historical, and SFnal; appearing in both world wars, the Old West, Ancient Rome, and Australia; reloaded, remorseless, triumphant, fallen, steampunkish, cackling, and cat-owning. But associating the sleeping god with a season actually seems particularly appropriate. Cthulhu awakens, bringing change and art and revolution, when the stars are right. This happens repeatedly, cyclically, and with possibilities for the ultimate inversion open each time. This seems, at the very least, mirrored, in the gifted hour’s opportunity for communion and oblivion.

The precise extent of those opportunities seems ambiguous. How personal is what happens to the narrator, and how much is he enabling some world-shifting change? (I note that Martin clearly has had more “communion” with Jasper-as-he-is-now than he admits, given his own sores. Is he luring Narrator in deliberately, as an additional or maybe replacement sacrifice? Magic 8-ball says, “It is decidedly so.”) It’s not clear if Narrator survives giving himself away in any meaningful sense, or if his attraction/repulsion to his ex has reach its ultimate cosmic conclusion in “the total unity of matter that only oblivion could provide.” I’m a little fuzzy about whether Milford survives, or indeed anything beyond it—but it’s equally possible that everything beyond the cosmoscope goes untouched, and that oblivion is strictly enthusiastic-consent-based.

This Apocalypse Maybe reminds me of stories from Ashes and Entropy, particularly Geist’s “Red Stars/White Snow/Black Metal.” The “Victory Over the Sun” soundtrack seems like the kind of thing Narrator might have spun as a late-night college DJ. He may not be up for a gonzo journalism road trip, but digging into some small-town history before getting seduced by the hungry void? Oh yeah. He is absolutely swiping right on Geist’s “sequestered divine spark rising up to immolate everything before darkness takes us all.”

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 9-10. We’re not in Narnia, any more, Toto, and we’re seriously convinced that there’s no place like home.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Two, it names a microscopic journey through tiny universes or worlds.

Okay- now I’m flashing on Disneyland’s Adventure Through Inner Space ride. Could Walt have been summoning Cthulhu? Is Mickey Mouse really a Great Old One?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adventure_Thru_Inner_Space

The temporal dislocation caused by crossing the international dateline was used as a major plot-point by Jules Verne (in Around the World in 80 Days).

Honestly? I love crossing the International Date Line, which I have done on many occasions since I regularly traveled to East Asia and Australia for work before I retired. I met my wife in South Korea, and what I don’t like is having my in-laws on one side of the Date Line and us on the other. It constantly confuses us, and it confuses them, resulting in my mother-in-law often calling at 3:00 AM in New Jersey. Crossing it is a lot easier than staying in touch with somebody on the other side of it.

But the International Date Line is NOTHING compared to Arizona. That state (except for the Navajo who live in it) does not observe daylight saving time. One of my oldest and dearest friends lives in Flagstaff and it is fraught at certain times of the year to call at a time we’ve both agreed on because the time differential changes twice a year as we go into and out of DST.

What would I do? I’d trash standard time, rename daylight saving time as standard time, and have that be the time all year long. I am not saying this just because the days are longer, because I know better than to be swayed by that. Even on a short day, I just like the way the light falls. My wife felt that way even before we’d met.

Working in Stockholm for a few weeks in midsummer was fun. The sun rose at 3:00 AM. The city was also deserted because everybody in Sweden goes on vacation in midsummer. It was like The World, the Flesh and the Devil or The Quiet Earth or Night of the Comet, but without, you know, the zombies.

@2. Elliot

Also in a soft SF detective story by Arthur C Clarke set on Mars in which a thief of a precious alien artifact in a museum on Mars’ version of the IDL was caught because, having planned to make his theft on the weekend, he was astonished when museum staff opened the museum on what was supposed to be Sunday. In his hotel just a couple of streets away it was, but in the museum it was still Saturday.

My Grandfather (born 1908, Scots) used to talk about God’s Time and Government Time. (They had Double Summer Time during the war, which Granddad referred to as “Daft Time”).

Personally, I’m team God’s Time. Noon should be at noon – and the thought of the dark morning you’d get in winter in northern latitudes on permanent British Summer Time is pretty grim.

As someone who grew up in the North-Eastern Pennsylvania woods, I really love the location. Our woods are old but well-lit, full of vigor (and fauna) and they’re magical in a way that’s not, to me, malicious like woods further North can be. That tone matches the energy of the character’s communion. And the way the language changes over the course of the story! No wonder Jasper is a dancer, this whole story is written like a dance. Absolutely wonderful.

Europe wanted to abolish DST this year, but the countries can’t agree whether to keep summer time or winter time (those who make the decision seem to know nothing about astronomy, permanently using the wrong time makes no sense).

One of Asimov’s Black Widower mystery stories had the change to DST giving a murderer an alibi. Apparently, he had to tweak the title so as not to give away the solution.

PamAdams @@@@@ 1: I have strong headcanons around this, due partly to the experience of reading the Illuminatus Trilogy in line at Disneyland back when you had to wait in long lines at Disneyland, and partly to having once stayed in Walt Disney World’s Aztec-themed hotel. Where there was a volleyball court. Labeled “ball court.” (Is an Aztec-themed resort a culturally-dubious decision, especially in Florida? Yes. Did I play volleyball? No.)

BillReynolds @@@@@ 3: To clarify, I love crossing the date line, as the end result is being in Melbourne, one of my favorite places on the planet. (I realize the end result can be other places too, but that’s where I’ve gone so far, and most of the relevant places have platypodes in any case.) I find it brain-twisting to think about the date line, and particularly surreal when I’m suffering from that much jet lag. Planets are really big and also round, and transpacific flights tend to highlight the degree to which I do not actually have my head around what it means to live on one. One of these years I’ll travel to latitudes that get extremely high or low amounts of sun, and twist my un-planet-minded brain in a different way!

MR James’ cosily creepy After Dark in the Playing Fields has the idea of “true midnight” as a plot point. The narrator, after seeing thing man was not meant to wot of always makes sure to get off the playing fields of Eton by “true midnight” (1 am British Summer Time) so as to avoid an unpleasant encounter with the Fae.

You probably have a long list of books you want to get through for this Reading the Weird series, but if you need suggestions–try The Girl in a Swing by Richard Adams. Definitely a departure for the people who only know him for Watership Down, and lots of the mysterious, the otherworldly, and the downright terrifying. One of those books that gets put on lots of different shelves in the library because no one quite knows how to classify it.

If you insist on true midnight you have to use local time, the right time zone is too inaccurate if you aren’t on the same longitude as the reference place for the time zone.

There’s a great Duck Comic by Don Rosa called “The Island at the Edge of Time”, that uses the International Date Line as a major plot point.

MA @@@@@ 11: We do have a long list, but consider this my big-eyes emoji at an intriguing Adams recommendation. Mostly when I hear people talking about his stuff, it’s coming with the “not as good as Watership” caveat rather than just “different from.”

@13: It’s interesting that that comic came out about a year before Umberto Eco’s The Island of the Day Before, which also uses the International Date Line. Probably a meaningless coincidence.

The Girl on a Swing is quite completely different from the other books Richard Adams is known for, and beautifully weaves together a number of traditional spooky-story themes into one seamless whole – be careful what you say to a stranger, wishes come true have a price to pay, truth will out, the dead want their due. It’s been a long time since I read it, but I recall it really catching the sense of the eerie, and certain parts are still stuck in my memory, like the dog with Death on his collar, or the narrator trying to stay coherent through his courtroom testimony.